What would it take for Alexandria to preserve affordable housing like DC and San Francisco?

Two cities have preserved thousands of affordable units through strike funds and small sites programs. Here's what worked, what it cost, and which strategies Alexandria could implement.

Editor’s note: This is the third in a series examining Alexandria’s Housing 2040 affordable housing preservation plan. Read my previous coverage on the city’s 40-strategy proposal and my explainer on affordable housing terminology and income levels.

Alexandria wants to preserve thousands of affordable housing units before they disappear. Is it actually possible to do this at scale?

Yes—but only with substantial resources, sustained commitment, and sometimes state authority that Virginia hasn’t granted its localities.

Washington, D.C., and San Francisco have spent the past decade proving that affordable housing preservation works. Their experience offers both a roadmap and a reality check for what Alexandria would need to succeed.

Washington, DC: Scaling preservation through crisis

When DC Mayor Muriel Bowser launched the Housing Preservation Fund in 2017, she committed $10 million in seed money, according to DC’s Department of Housing and Community Development. That initial investment, combined with private and philanthropic capital, grew into a $184 million fund that has preserved thousands of units.

The model: Provide bridge financing—short-term, low-cost loans—that let nonprofit developers move quickly to acquire buildings before market-rate investors can. Once acquired, nonprofits secure long-term funding through tax credits and other sources while keeping tenants in place.

According to DC’s housing department, the fund’s three managers have provided more than $178 million in financing for 40 projects preserving 2,594 affordable housing units, with Capital Impact Partners alone financing 14 projects preserving 1,587 units.

The 2024 expansion

By 2024, DC faced new pressures. According to the city’s 2024 Consolidated Request for Proposals, approximately 22,000 units, representing 48,000 residents, were at risk of foreclosure due to delinquency, with more than 80% of properties not receiving sufficient rent to cover their mortgages or maintenance expenses.

Rather than retreat, DC doubled down. In 2024, the city selected 69 projects to receive up to $144 million in funding to preserve nearly 8,000 units of housing, of which over 7,700 are affordable—the most significant Housing Production Trust Fund investment in affordable housing preservation since the fund’s inception.

The complementary tools

DC’s preservation success doesn’t rely solely on the fund. The city also benefits from:

TOPA (Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act): Enacted in 1980, this law gives tenants the first right to purchase their building when sold, or to assign that right to nonprofits. According to PolicyLink and advocacy groups, the law has preserved more than 4,300 rental homes, with one-third of all multifamily transactions in 2014-2015 happening through TOPA.

$100 million annual Housing Production Trust Fund: According to Mayor Bowser’s office, the mayor has committed this amount annually, more than any city per capita in the country.

Dedicated preservation staff: DC appointed its first Affordable Housing Preservation Officer in 2018, creating capacity to identify at-risk properties and coordinate efforts.

The challenges that remain

Even DC’s robust system isn’t perfect. According to February 2024 testimony from the DC Fiscal Policy Institute to the DC Council, projects that received acquisition financing through the Preservation Fund will need roughly $58 million in gap financing to preserve over 1,400 units between fiscal years 2024 and 2026. Some projects have been waiting so long that owners are forced to sell properties they acquired to preserve affordability.

What this suggests: Bridge financing must be paired with permanent financing sources, or preservation efforts stall midstream.

San Francisco: Targeted preservation of small buildings

While DC created a broad strike fund, San Francisco focused on the buildings most vulnerable to displacement: small multifamily properties with 3-25 units.

The Small Sites Program, launched in 2014, provides acquisition and preservation loans to nonprofits purchasing rent-controlled buildings before they’re sold to investors who might evict tenants or dramatically raise rents.

The results

According to a March 2025 announcement from the Mission Economic Development Agency, the program has deployed over $378 million in funding to preserve 69 buildings comprising 843 residential units for low and moderate-income households and 50 commercial spaces.

MEDA, one of the most active participants, acquired two major properties in March 2025, according to their announcement: 2059-2061 Mission Street with 35 residential and four commercial spaces, and 2901-2929 16th Street with 63 residential and eight commercial spaces.

The cost-effectiveness argument

According to San Francisco Planning’s analysis, as of February 2018, the average acquisition cost per unit was $360,568, with average rehabilitation costs at $65,339 per unit—roughly $426,000 total in one of America’s most expensive markets.

That sounds expensive until you compare it to new construction. According to preservation advocates, Bay Area acquisition-rehabilitation projects cost 50-70% of new affordable housing production, making preservation cost-effective relative to building new.

Preservation also offers immediate impact: tenants stay in place rather than waiting years for new construction.

The persistent challenges

According to San Francisco Planning, San Francisco’s inflated market prices force organizations to compete at high costs, limiting the number of buildings that can be acquired at any given time.

The city has tried to address this through reforms and increased funding, but the fundamental tension remains: In hot real estate markets, preservation competes with market forces that are difficult to overcome without substantial public investment.

Minneapolis: When political will falters

If DC and San Francisco show what’s possible with resources and commitment, Minneapolis demonstrates what happens when political consensus can’t form.

Since 2019, Minneapolis has attempted to enact a Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act modeled on DC’s successful law. The city commissioned comprehensive studies, developed draft ordinances, held community meetings, and built advocacy coalitions. As of October 2025, the measure has never passed.

According to the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, Council Member Jeremiah Ellison reintroduced a version of the policy in 2024, but it has since stalled, despite data from the Minnesota Department of Administration showing 76.9% of white households in the state own their homes, compared with 29% of Black households—one of the nation’s worst homeownership gaps.

Why it stalled

The Minneapolis experience highlights several barriers:

Organized opposition: The Minnesota Multi Housing Association and Minneapolis Area Association of Realtors mounted sustained campaigns arguing TOPA would complicate transactions and deter investment.

Competing priorities: According to Minneapolis Star Tribune reporting, Minneapolis also debated rent control, and city staff argued rent stabilization should come first.

Funding uncertainty: Even if TOPA passed, advocates acknowledged needing city subsidies to help tenant cooperatives finance purchases—costs that were never specified or allocated.

Legal concerns: Staff cited property rights legal questions that needed resolution.

What this suggests: Policy authority without implementation funding creates symbolic rights rather than practical tools. DC’s TOPA works because nonprofits can access preservation fund capital actually to purchase buildings.

Applying these lessons to Alexandria

These case studies suggest specific strategies Alexandria could pursue—and reveal the resources required to make them work.

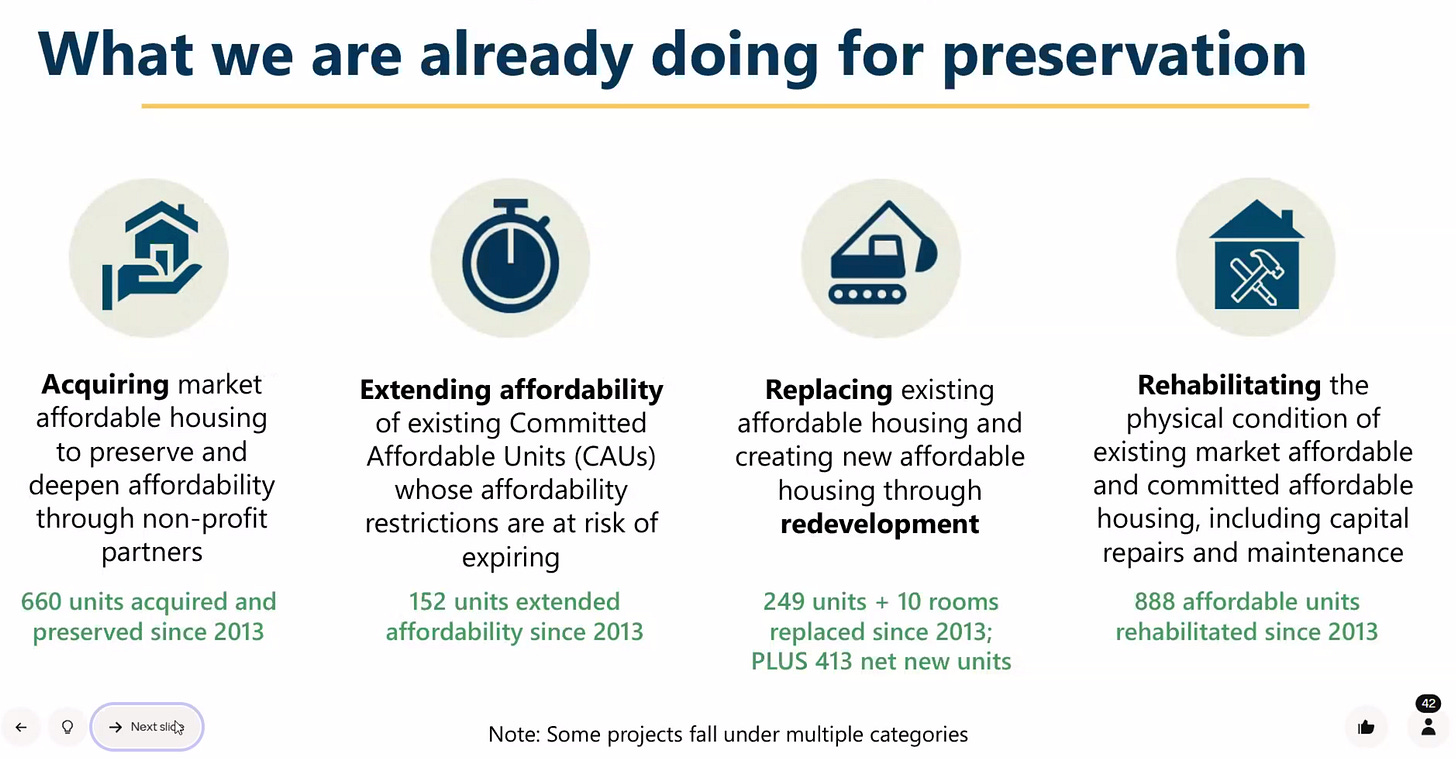

What Alexandria is already doing

Before examining what more Alexandria could do, it’s worth recognizing what the city has already accomplished. Since 2013, Alexandria has preserved affordable housing through multiple strategies—demonstrating both local capacity and the challenges of scaling up.

According to Monday’s presentation by housing analyst Christopher Do, Alexandria has:

Acquired or helped preserve 660 units through nonprofit partnerships.

Extended affordability commitments for 152 units at risk of expiring.

Replaced 249 units while creating 413 net new units through redevelopment (662 total).

Rehabilitated 888 affordable units in aging buildings.

The city’s four major case studies illustrate different preservation models:

1. Acquisition: Parkstone Alexandria

The deal: Housing Alexandria acquired 326 units for $110 million total

City investment: $8 million

Result: Preserved 130 units at 60% AMI, 114 units at 80% AMI, remainder at market rate

Key lesson: Significant leverage—$8M city funds helped secure $102M from other sources

2. Extension + Redevelopment: The Heritage

The deal: 750-unit mixed-income development

City investment: $0 in direct subsidy

Result: 140 replacement affordable units at 40% AMI, 55 new affordable units

Key lesson: Zoning tools and density bonuses can preserve affordability without direct city funds

3. Replacement: Elbert Avenue

The deal: Community Lodgings Inc. redeveloped into 91 units

City investment: $3.8 million

Result: Deep affordability—9 units at 30% AMI, 15 at 40% AMI, 22 at 50% AMI, 45 at 60% AMI

Key lesson: Focus on serving lowest-income households (as low as 30% AMI)

4. Rehabilitation: Landmark Towers

The deal: Private owner rehabilitation of 154 units

City investment: $2.5 million

Result: Building upgraded with rent increase caps and right of first refusal

Key lesson: Can work with for-profit owners who commit to affordability restrictions

5. Redevelopment with permanent affordability: Samuel Madden Homes

The deal: Fairstead broke ground in November 2025 on $120 million redevelopment

City investment: [specify amount if known, or note city is owner and lender]

Result: Replacing 66 aging townhomes with 207 units at 30-80% AMI—triple the density

Key lesson: Permanent affordability commitment; right to return for all residents; one-for-one replacement policy

According to my November coverage, the development uses what Fairstead described as a “9, 4 hybrid” financial structure with multiple partners, including Boston Financial, Freddie Mac, Virginia Housing, and Sterling Bank. Freddie Mac alone invested more than $50 million in the project.

The project demonstrates Alexandria’s capacity for complex, large-scale affordable housing development that preserves communities while significantly increasing the number of affordable units. It also shows the importance of right-to-return policies—all 66 families who lived at Samuel Madden have a guaranteed right to return when construction completes in fall 2027.

What the numbers reveal

These projects demonstrate several things:

City investment averages $24,500 per unit (using Parkstone as the model), but total project costs average much higher when including all funding sources. The city’s role is typically providing gap financing that unlocks larger pools of capital.

Leverage ratios vary widely: Parkstone achieved roughly 13:1 leverage ($8M city → $110M total). Elbert Avenue was closer to 1:1 ($3.8M city for a smaller project). Heritage required no direct city subsidy by using regulatory tools instead.

The pace matters: Preserving roughly 1,562 units over 12 years = approximately 130 units per year. But Monday’s presentation showed the city is losing an estimated 400+ market-affordable units annually. The city is preserving housing, but not fast enough to match the rate of loss.

What’s working well

Several elements of Alexandria’s preservation work have proven successful:

Strong nonprofit partners: Housing Alexandria, AHDC, Wesley Housing, and Community Lodgings Inc. have demonstrated the capacity to execute complex preservation deals.

Diverse toolkit: The city has used acquisition, extension, rehabilitation, and redevelopment—not relying on a single approach.

Strategic use of city funds: Eight million dollars in city investment helped preserve 326 units at Parkstone; $3.8 million supported 91 deeply affordable units at Elbert Avenue. The city is strategic about where to deploy limited resources.

Right of first refusal: Already implemented on some projects like Landmark Towers, giving the city or nonprofits the option to purchase if owners decide to sell.

Relationship with property owners: Successfully partnered with both nonprofit and for-profit owners willing to accept affordability restrictions.

The scaling challenge

The question isn’t whether Alexandria can preserve affordable housing—the track record proves it can. The question is whether the city can scale up from preserving 130 units per year to preserving 400+ per year to match the pace of loss.

That would require:

Triple the current pace of preservation activity.

Triple the funding (roughly $10 million annually instead of $3-4 million).

More nonprofit capacity or regional partnerships.

Faster deployment of capital (bridge financing model).

More properties in the pipeline at any given time.

The infrastructure exists. The experience exists. What would need to change is primarily the scale of resources committed to preservation relative to the scale of the challenge.

Current costs based on recent data

DC’s 2024 preservation: According to DC’s housing department, $144 million to preserve 7,700 affordable units = roughly $18,700 per unit (with significant leverage of other funding sources).

San Francisco’s program: According to MEDA, $378 million deployed for 843 units = roughly $448,000 per unit in SF’s expensive market.

Alexandria’s Parkstone example: $8 million city investment for 326 units = $24,500 per unit in city funds, with nonprofit and private capital covering the remaining $102 million.

What preserving 2,000 units would require

If Alexandria aimed to preserve 2,000 market-affordable units over 15 years—less than a third of what’s been lost since 2000—at the Parkstone rate:

$49 million in city investment ($3.3 million annually).

Plus ~$147 million from nonprofits, LIHTC, bonds, and other sources.

Total project cost: ~$196 million.

For context, Alexandria’s FY2026 budget includes $17.3 million for all housing initiatives: production, preservation, rental assistance, homeownership programs, and operations.

DC, by comparison, spends $100 million annually on housing for a city roughly three times Alexandria’s size. On a per capita basis, Alexandria would need to approximately double its entire housing budget to match DC’s commitment level.

Preservation strategies available through local action

Most of Alexandria’s proposed preservation strategies don’t require Virginia General Assembly authorization and could be implemented through City Council action:

1. Preservation strike fund (DC model)

Provide bridge financing for quick acquisition

Start with $5-10 million, leverage 3-4x with private capital

Partner with regional CDFIs

Action needed: City Council appropriation

2. Small sites acquisition program (SF model)

Target vulnerable 2-49 unit buildings

Estimated cost: $300-400K per unit (lower than SF due to cheaper market)

Action needed: Already proposed in Housing 2040 recommendations—needs dedicated funding

3. Right of first refusal in city-funded deals

Apply to all city-funded housing deals

Administrative, minimal cost

Already doing on some projects (Landmark Towers)

Action needed: Expand systematically through policy

Note: The city is seeking state legislative authority for right of first refusal on committed affordable properties not receiving city funds, but can implement ROFR locally on properties where city provides funding

4. Anchor institution partnerships

Joint ventures with hospitals, universities, churches

Shared/leveraged capital

Action needed: Already proposed in recommendations—requires negotiation and relationship-building

5. Rehabilitation assistance programs

Provide funding to property owners in exchange for extended affordability commitments

Property tax relief as financial incentive

Action needed: City Council appropriation and policy framework

These strategies are legally available to Alexandria today through City Council action.

Tenant protection strategies requiring state approval

While preservation strategies are largely under local control, the most powerful tenant protection measures require Virginia General Assembly authorization:

1. Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act

Would need enabling legislation

Virginia’s Dillon Rule prevents local TOPA without state approval

Would apply to all properties, not just city-funded ones

2. Just cause eviction requirements

Currently requires state approval

Alexandria cannot implement locally under Dillon Rule

3. Rent stabilization/anti-gouging measures

Rent control banned at state level

Would require state law change

4. Mandatory landlord-funded relocation assistance

Requires state legislative authority

City can offer relocation assistance programs locally, but cannot mandate landlords pay

5. Rental registry with enforcement power

Requires state authorization

City can track city-funded properties but cannot require all landlords to register

6. Enhanced habitability enforcement

Local authority to sue landlords for unsafe conditions requires state approval

7. Rent payment plan requirements

Mandating landlords offer payment plans before eviction requires state authority

8. Limitations on fees

Restricting mandatory charges (internet, pet fees, amenity fees) requires state approval

Alexandria’s state delegation would need to carry these bills through the January 2026 General Assembly session. The political challenges are significant in a state with strong property rights traditions, but not impossible—Minnesota already grants manufactured home park residents the right of first refusal when parks close.

Overcoming the implementation challenges

Cities that have succeeded in preservation have addressed several common obstacles:

Challenge 1: Federal funding uncertainty

DC and San Francisco built their programs with local funding as the foundation, treating federal sources as supplementary. This insulates programs from federal policy shifts.

Alexandria’s situation: Housing Director Helen McIlvaine acknowledged “the financial uncertainty around the federal government” as a planning consideration during Monday’s community meeting. Building local funding capacity would reduce dependence on uncertain federal sources.

Challenge 2: Nonprofit capacity

Preservation at scale requires experienced nonprofit developers with strong balance sheets, real estate expertise, and property management capacity.

Alexandria’s assets: The city has established nonprofits, including Alexandria Housing Development Corporation, Housing Alexandria, Wesley Housing, and Community Lodgings Inc. The question is whether they could scale to DC-level operations, or whether regional partnerships would be needed.

Challenge 3: Speed vs. deliberation

DC’s bridge financing succeeds because it allows rapid deployment. Government processes typically move slowly. How to balance speed with accountability?

Possible solution: Pre-qualify nonprofit partners, establish clear criteria, delegate acquisition authority within parameters, and require post-transaction reporting.

Challenge 4: Permanent financing gaps

Bridge loans must transition to permanent financing, but that funding isn’t always available when needed.

Possible solution: Coordinate preservation fund deployment with Housing Production Trust Fund cycles, set aside a dedicated HPTF allocation for preservation projects, and create a pipeline management system.

What happens next in Alexandria

The draft preservation recommendations are scheduled to go to the Housing Affordability Advisory Committee on December 4. Public comments are accepted through December 30 at alexandriava.gov/HousingPlan. A final community meeting is scheduled for February 28, 2026, followed by City Council hearings in spring 2026.

Several key decisions lie ahead:

Budget decisions (Spring 2026): Will City Council allocate funding for preservation in the FY2027 budget? How much? For which strategies?

State legislative session (January 2026): Will Alexandria’s delegation introduce tenant protection legislation? Will they coordinate with other Northern Virginia localities for regional push?

Implementation planning: Which strategies will be prioritized? What’s the timeline? Who will manage implementation?

Partnership development: Which nonprofits, CDFIs, and anchor institutions will participate? What are their capacity constraints?

The city is planning to continue the trajectory started with projects like Parkstone—$8 million in city investment, helping preserve 326 units. The question is whether this project-by-project approach can scale to address the estimated 400+ units lost annually to market-rate conversion.

The core question: Scale and urgency

DC and San Francisco prove that affordable housing preservation works when cities commit substantial, sustained resources.

DC started with $10 million in 2017. By 2024, according to the city’s housing department, the city was deploying $144 million in a single funding round to preserve 7,700 units.

San Francisco launched Small Sites with $3 million in 2014. By March 2025, according to MEDA, the program had deployed $378 million, preserving 843 units.

Both cities have preserved thousands of units—but both also acknowledge they’re racing against powerful market forces that continue eroding affordability despite their efforts.

Alexandria’s situation is similar: losing 400+ market-affordable units annually while preservation capacity remains limited. The December 30 comment deadline and February 28 community meeting offer opportunities for residents to weigh in on priorities and resources. The real decisions come later: in budget appropriations, in state legislative votes, in how preservation is prioritized relative to other city needs.

DC started small—$10 million became $184 million through sustained commitment. San Francisco’s $3 million pilot became a $378 million program. Alexandria has the foundation: experienced nonprofits, successful preservation projects, and proposed strategies. The question is whether it can build on that foundation at the pace and scale the challenge requires.

Read more in my Housing 2040 series: Alexandria proposes 40 strategies to preserve affordable housing, and What does ‘affordable housing’ actually mean? A guide to Alexandria’s housing categories.